Nature is waiting for you

Physical, mental and social: nature is good for us, all of us. And it’s right there, waiting for us.

Dappled light dances under your feet, mirroring the rhythmic rustling of the leaves overhead. Your heart rate slows. Your breath deepens. A smile creeps across your face. You can’t remember what was on your to-do list. The irritation after a no-progress meeting fades into oblivion. Worrying about this, that and everything in between seems immaterial. Just 10 minutes ago you were slamming the door in frustration. Now you’re in your happy place. That place is nature. It needn’t be on the other side of the world or a day’s drive away. It can be a tree-lined street on the way home from work, the park by your child’s school or the nature reserve that’s just outside the city boundary. Spending time in nature is good for us and it needn’t require Herculean effort to accomplish.

From the creation of the first nature reserves, city parks and the days of well-to-do aristocracy heading off to the countryside to “take the air”, we’ve known for years that spending time in nature is good for our health. Way back in 1865, famous landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted – who designed New York’s Central Park – wrote

It is a scientific fact that the occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character is favourable to the health and vigour of men and especially to the health and vigour of their intellect.

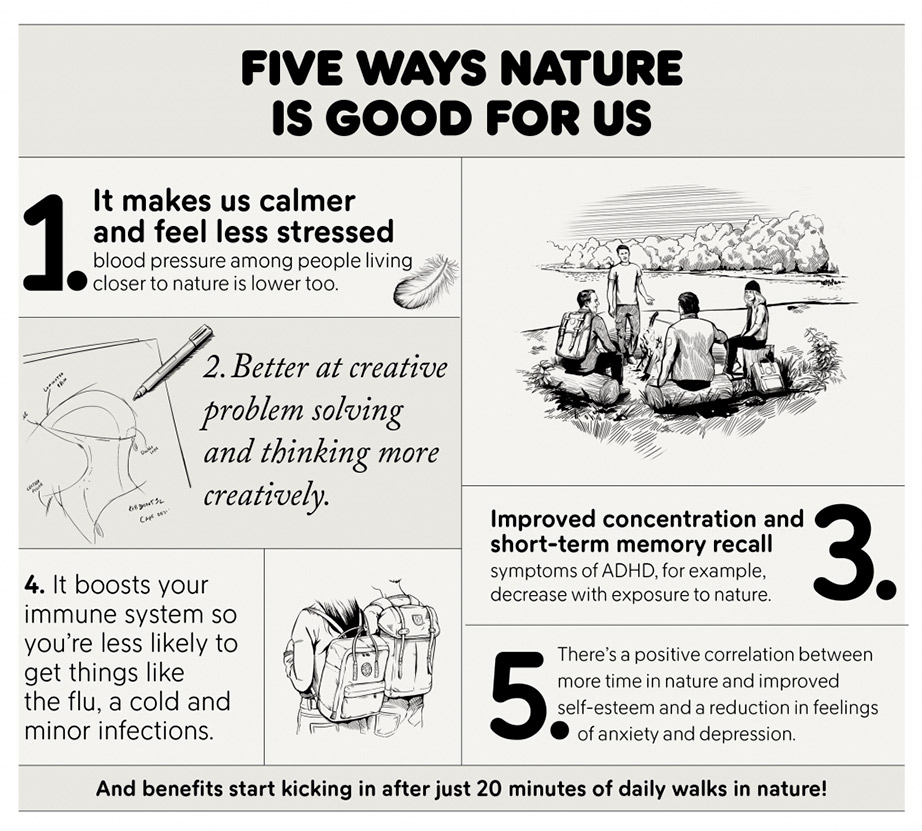

Despite his statement to the contrary, there weren’t actually any “scientific fact(s)” proving the benefits of nature to human health at that time (it was more just a general feeling or innate knowledge). But now, more than 150 years later, there are. Studies conducted everywhere from Japan to Finland, the US and the UK have shown the benefits of nature to be manifold and multifaceted. They range from the physical to the mental to the societal. It’s not really known why, but the correlation between human health and well-being and time spent in nature is overwhelmingly positive.

It's good for our bodies

Often when we think of nature, at least nowadays, it’s not just about being there. It’s usually about doing something there. So the fact that people with access to nature – be it urban parks or rural trails – are less likely to be obese or overweight shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. But according to the Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP), the benefits actually extend further than a reduction in people’s waistlines. It cites results such as lower blood pressure in pregnant woman, a 16% lower risk of dying for men living in deprived areas closer to green space, and higher birth weights and larger head circumferences in babies born in places with abundant green areas, as evidence for the benefits of living close to nature.

And for our minds

While the physical benefits are tangible and easily seen, the mental ones are more nuanced though no less apparent. Doctors have believed in the mental healing of nature since the 19th century. Back then it was fashionable for doctors, particularly those practising psychiatry, to recommend a week breathing the fresh air of the Swiss Alps, coastal Dorset or rural New England. Now doctors don’t necessarily prescribe an expensive week away rubbing shoulders with Swiss skiers or Dorset fishermen, but they do encourage patients to spend more time outdoors. UK charity Mind has been using what it calls Ecotherapy to help improve patients mental health for several years. The practice involves patients spending time “connecting” to nature, mostly through supervised group sessions combined with cognitive behavioural therapy. Activities range from conservation projects to simply walking through nature together, discussing the landscape and flora and fauna. It works in a similar manner to Japan’s “forest bathing” or exercising along Finland’s “power trails”. Patients consistently report a reduction in feelings of depression, anxiety, anger and stress and improvements in self-esteem and emotional resilience. The IEEP highlights a study conducted by Alnarp Rehabilitation Garden in southern Sweden. It tested a nature-based treatment for people recovering from stress-related mental disorders, stroke and war neuroses. After just one year of rehabilitation the effects were clear: an improvement in well-being, reduced stress and increased positivity. There were also knock-on effects that were more wide-reaching: the costs for primary care dropped by 28% and days spent in hospital fell by 64%.

It’s even good for society

These broader societal benefits are now being studied. And they don’t just include reduced medical bills and health care costs. According to Patrick Ten Brink, the director of the Institute for European Environmental Policy, “giving communities an active right to nature will improve health, social integration and be a major step to reducing social and health inequalities”. Research conducted by the IEEP, on behalf of Friends of the Earth Europe, highlights that access to nature and shared green spaces can lead to increased social cohesion and reduced social tension. It gives people a shared sense of place and identity, which goes beyond racial, ethical and socio-economic boundaries.

What’s the catch?

This all sounds very utopian: the answer to all our problems is right there outside the window. We just have to get out there. But it’s not that simple. 70% of the world’s population will be urban by 2050. Europe has already surpassed this threshold with a full 80% predicted to live in cities by 2020. As open areas are eaten up by housing, finding space for nature that’s close to home is proving more difficult. Seeing as all the benefits of living near to nature only kick in when the distance from green space is less than 300m – with the benefits dropping off once you cross the 1km mark – urban planners are faced with some pretty monumental challenges. How do you provide easily-accessible nature to growing urban populations? Cities are already sprawling into each other. With the pressure to build as close as possible to a city’s CBD and reduce the distance people have to commute by car, a catch 22 conundrum presents itself.

Edinburgh has 49.2% green space - the most of all UK cities.

According to human geographer and author Dr. Klas Sandell, the solution is sustainable development. The United Nations defines this as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs". This requires society to look more holistically at development. “We need to find a way to live, work and thrive with nature,” explains Klas. “Protecting nature is just the first step.”

Sweden (and Norway and Finland, for that matter) sets a very good example. The Right of Public Access – allemansrätten in Swedish – has helped shape Swedish people’s views of nature. “Here nature isn’t so much of a ‘wilderness’, as in it’s far away. It’s more about general outdoor recreation and encounters in a natural landscape,” says Klas. “It’s about simplicity in terms of equipment and activities – a stroll in the forest instead of an expedition in the wilderness. And it’s about freedom of choice.”

This idea about keeping things simple seems to reflect the science. The research suggests that frequent visits to nature – however small – and living close to green areas are more beneficial in the long term than infrequent expeditions in the wilderness. Some cities in Europe are already implementing strategies to ensure their residents live no more than 300m from green areas, Oslo in Norway and Victoria-Gasteiz in Spain are two examples. “The evidence is strong and growing that people and communities can only thrive when they have access to nature,” explains Robbie Blake, nature campaigner for Friends of the Earth Europe. “We all need nature in our lives. It gives us freedom and helps us live healthily.”

The more, the merrier

There’s proof that once you start a love affair with nature, it’ll never end. In fact, your love and appreciation of it will thrive. Research has shown there’s a positive correlation with the amount of time we spend in nature and our willingness to protect and preserve it (and spend even more time in its embrace). A month-long study in the UK by the Wildlife Trust and Derby University, called 30 Days Wild, found that not only did regular activity in nature increase the number of people reporting their health as “excellent” by 30%, it also showed that people are more likely to care for their local environment and value its positive impact and thus protect it.

Balancing the scales

But in comes that catch 22 situation again. If we all spend more time in nature, which in turn makes us want to protect it, how do we manage the growth of the world’s population and the migration into cities?

“It’s about balance,” says Klas. “We know that sustainable development relies upon public acceptance of changes in consumption and lifestyle. If we establish multipurpose land use where forestry, infrastructure, agriculture and dwellings are combined with leisure, conservation and education, it’s reasonable to believe that this could form a more solid basis for a sustainable development; it’s a better basis than a view of nature as something located at special places, sometimes visited but only for aesthetics and adventure – not as a crucial basis for all aspects of human living.”

So what can we do?

How often do you step out in nature? Daily? Weekly? Finland now recommends five hours of nature time per month, divided up into short, regular visits. Researchers there found that a change in mood and attention span can happen in just 40 minutes. The 30 Days Wild challenge in the UK found it’s not just about the time you spend in nature, but what you do there: touching the bark of a tree, watching bees buzzing around their hive, dipping your toes in a lake, sharing the experience with others. This is why both with Mind’s Ecotherapy and along Finland’s Power Trails people are encouraged to interact with nature to get the most out of it. And frequent short stints in nature like this are more likely to encourage longer, more immersive and rewarding escapes into the great outdoors. This creates feedback loops which spill over from the individual and benefit society as a whole.

When we launched Fjällräven Classic in Sweden in 2005 the aim was to encourage more people to trek in the Swedish mountains. But it has become so much more than that. As more people joined us, we realised that Fjälllräven Classic was about inspiring people to spend more time in nature generally. By training for the trek they would walk through their local nature reserves and parks. They would cajole their friends and family into joining their adventures. And eventually they motivated us to expand Fjällräven Classic to Denmark, the US and Hong Kong. What started as a low-key wilderness experience for people already pretty used to time outdoors, has become the kick-starter to spending more time in nature for everyone. “I’m passionate about inspiring others to experience nature,” says Carl Hård Af Segerstad, Fjällräven Classic event manager. “Getting out in nature has so many positive associations on both an individual and societal level. It’s good to do physical exercise of course, but it also shows you what’s important in life. I believe it’s vital to experience nature first hand because you can’t care for and protect something you’ve never experienced.”

We’d love you to join us for Fjällräven Classic, of course, but you don’t need to do a multi-day trek to begin your journey into nature. As the research shows, just 40 minutes in nature can bring welcome benefits. All you need to do is open the door and walk out. Nature will do the rest.